History – Howarth of London

T. W. Howarth & Co. first came into existence in 1948 when members of three families united to form the company. The three families were the Mooneys, the Ingrams and the Howarths, each of which had been involved in woodwind instrument manufacture and repair for many years prior to 1948. The founding directors of T. W. Howarth & Co. were Thomas Howarth, George Ingram and Frederick Mooney.

Frederick Mooney was born in 1903, the youngest of eight children, six boys and two girls. In this large family the boys were encouraged to follow their father and grandfather into the musical instrument making trade, while the girls successfully followed the female line into dressmaking for the aristocracy. Fred’s father Thomas and his grandfather Frederick had both worked for the military musical instrument makers, Distin, and the indenture reproduced on the inside front cover details Thomas Mooney’s apprenticeship to the company in 1859. Fred learnt his trade from a number of instrument repairers and assemblers operating between the wars including a period at the Premier Drum Company and at the band instrument maker Besson. At Besson he specialised in making clarinets and during his time there, in 1934, Boosey & Hawkes acquired an interest in the company.

The Howarth family began their involvement with instrument making when George Howarth, Thomas Howarth’s father, moved down to London from Rochdale. Born in 1860, he was the son of a pastry cook, but he did not follow in the family trade and once he moved to London he became an apprentice at the flute makers Liddle. Unfortunately the business was sold before George completed his training. George then moved to Boosey & Co. where he continued to work with flutes. Boosey & Co. were later to amalgamate with Hawkes & Sons in 1930, to become Boosey & Hawkes.

In 1894, George left Boosey & Co. and began his own business, known as George Howarth, based in York Street in the West End of London. He lived above the shop where he worked and gradually earned a good reputation as a woodwind technician and repairer. He had two sons, James and Thomas who on leaving school both went into the family trade. Before joining their father at York Street, James worked at Hawkes & Sons as an instrument repairer and Thomas worked as a saxophone assembler at Emmanuel Lewin where saxophones were manufactured from imported French parts.

There is little information available about George Ingram’s family, but it is understood that he too came from a long line of instrument craftsmen. It is known that in the late 1920s he left school to start a woodwind instrument making apprenticeship with the Louis Musical Instrument Company. This apprenticeship was the last that Louis & Co. offered. Indeed, in later years George thought that his apprenticeship was probably the last official apprenticeship to be undertaken in this trade in England. Louis & Co., which only existed between the two World Wars, was owned by a consortium of musicians, led by Charles Draper, a respected clarinet player of the period. When George joined the company they were operating from premises on the Kings Road in Chelsea. Louis was considered the premier professional woodwind instrument maker of the pre-war period. Although they made clarinets and bassoons it was the Louis oboes, d’amores and cors anglais for which they were mostly remembered. After his apprenticeship George was employed by Louis as a keymaker and was justifiably proud of the beautiful hand forged keys he made for the oboes. A thorough and methodical man, George made meticulous notes on every instrument on which he worked, including how long he took to complete the work. These diaries can be seen today and give an amazing insight into his life and work. During the war years he even made a note of the number of working hours he lost on an instrument due to air raids.

At the onset of World War II in 1939, some instrument companies, including Louis and Rudall Carte, ceased trading leaving a number of skilled instrument technicians and repairers without work. Boosey & Hawkes continued to make band instruments and in addition Geoffrey Hawkes, a director of the company, managed to secure contracts for war work. This enabled him to employ many of these craftsmen including Frederick Mooney, George Ingram and Thomas Howarth. It was, therefore, at Boosey & Hawkes that the three first met. Another well known instrument technician taken on at the time was Charles Morley and he was interviewed for work on the same day as George Ingram. One of the many contracts taken on by Boosey & Hawkes was for the Bristol Aircraft Company, the manufacturer of Lancaster bombers. So between working on instruments Fred, Tom and George frequently found themselves involved in the manufacture of bomb doors and rear gun turrets for Lancaster bombers, and on bomb canisters.

When the war ended work returned to normal at Boosey & Hawkes. Tom left the company and set up on his own in a small repair shop in Seymour Place. George was approached by the owners of Louis & Co. and was asked to relaunch the business. But George wanted to start his own company; so he and the friends he had met at Boosey & Hawkes decided to make and sell instruments themselves.

Between 1945 and 1948 Fred and George continued to work for Boosey & Hawkes, but after work they would go to Tom’s workshops in Seymour Place and develop patterns and tooling for the manufacture of their own oboes. When they had finished the first oboe at the beginning of 1948 a name had to be chosen for the instrument. As they thought that Mooney, Ingram and Howarth might be mistaken for a firm of solicitors it was decided that the first oboe should be stamped with Howarth & Co., London, a name already familiar in the woodwind trade. It is not known how many prototypes they made, but the first oboe (serial number 1001) must have been of a very high standard as in April 1948 it was purchased by Edward Selwyn. ‘The Duke’, as he was known, was principal oboist in the BBC Symphony orchestra

Howarth & Co. began to flourish and quickly established a reputation for manufacturing fine quality instruments: oboes, oboes d’amore and cors anglais. Tom, Fred and George also tried to enter the clarinet market and between 1949 and 1952, 38 Howarth clarinets were produced. Unfortunately the hand-crafted manufacture could not compete in price with the efficient production methods used at Boosey & Hawkes, so it was decided that Howarth & Co. would concentrate on making oboes.

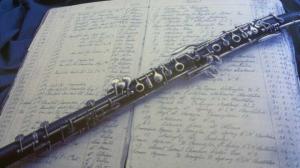

Beautiful hand-written ledgers, which read like a ‘Who’s Who’ of English oboists, were kept of every instrument made by Howarth; a practice still maintained today, but with slightly less elegant handwriting. As production started to grow the original trio were joined by Fred’s brother Bill Mooney and by 1951 the four partners were confident enough to become incorporated. The necessary money was found to convert Howarth & Co. to T. W. Howarth & Co. Ltd., with a share capital of £400 divided equally between Thomas Howarth, George Ingram and Frederick and Bill Mooney, the directors of the company.

In 1952, Thomas Howarth resigned after a disagreement with the other partners and his shares were divided amongst the remaining three directors. With his resignation there was some discussion about changing the company name. But Fred, George and Bill decided that the instruments were gaining a good reputation and that to change the name would involve unnecessary costs. Tom went back to working with his brother who was still trading under their father’s name, G. Howarth and Sons at York Street, W1. As Thomas Howarth was the leaseholder of the Seymour Place property, it became necessary to find new premises. A suitable shop and workshop was found nearby in Blandford Street.

The post war economic situation made it a difficult time to run the fledgling company. There was undoubtedly a demand for good quality instruments, but money for the arts was not a priority for re-building the country, and musical instruments had a purchase tax of almost 50%. Raw materials were very hard to find and the first instruments were made with solid silver keywork as nickel silver was not readily available.

Despite these difficulties, the company began to prosper. Over the first few years four oboe models were developed and offered to clients. All four models were prefixed with the letter ‘S’ which stood for solid silver. In later years when nickel silver and silver plate were used the ‘S’ remained. The S1 was a simple octave thumb-plate ring model oboe, the S2 a more modern version with semi-automatic octaves and the S3 (the American model) was an open hole conservatoire oboe with semi-automatic octaves. The S4 was exactly the same as the S3 but with fully automatic octaves, and was often referred to as the Eastern European model. The first S5 was made in 1950 and bought by Michael Dobson, who was later professor of oboe at the Royal Academy of Music. The S5 was the standard plateau conservatory model oboe and was often made with added thumb-plate for English players. The S5 was further endorsed in 1955 when Terence MacDonaugh bought that model. MacDonaugh was generally considered one of the finest orchestral oboists of the post war period and it was a major coup when he began to play a Howarth he even bought a second Howarth instrument in 1956.

Gradually additional staff were employed, including Pat Kanilly and Cecil Martin. Neither George nor Fred could play the oboe, so various players were engaged to help tune the instruments. Firstly the eminent oboist Horace Halstead tuned the oboes and in the 1960s Michael Dobson. Halstead was a highly respected player and in the 1930s played second to Leon Goossens in the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

He had considerable experience in oboe-making as he had previously been a director and tuner at Louis. The collaboration of Fred and George with these great players helped to develop the oboes. On the players’ advice the bore design changed and they also kept the company aware of the prevailing market trends.

There was another change in directorship of the company in 1960 when Bill Mooney died, leaving his shares to his brother. Thus Fred owned two thirds of the Howarth shares.

By this time it was thought that the days of the English thumb-plate system were losing out to the conservatoire system especially in the export market. Many students who had studied in Europe returned ‘converted’ to the conservatoire system. As a consequence, on the advice of Michael Dobson who had studied in France, the first Howarth student model, the S10, was offered only in conservatoire fingering. This theory was short lived and now the thumb-plate mechanism is predominantly used in England, often as an addition to a conservatoire instrument.

In 1968 the parade of shops on Blandford Street was redeveloped and new premises were found a few hundred yards away at 31 Chiltern Street; this site is still occupied by the company today. By the end of the 1960s T. W. Howarth & Co. Ltd. had achieved nationwide recognition and their oboes were used by oboists in many of the major orchestras.

Nigel Clark – Howarth of London