Description

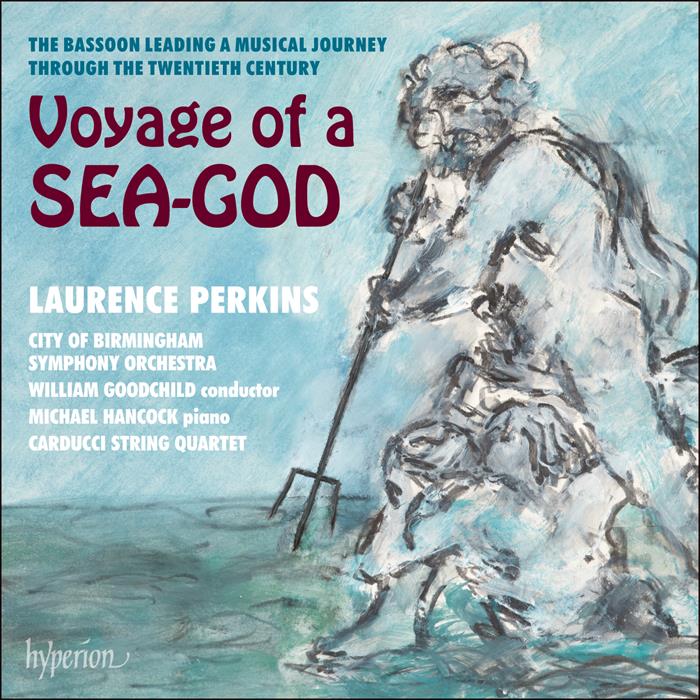

‘No composer has ever understood the qualities of individual instruments as did Mozart; neither has anyone, except Mozart, had such power in imparting a quality of ephemeral beauty … with the bassoon, it is like a sea-god speaking, and the most beautiful and elaborate fancies of Debussy, in ‘La Mer’, are not more evocative of the spray, of Neptune with his flashing trident, and of the tritons sounding their conch-shells.’

in Mozart (1932) by Sacheverell Sitwell

It was in the twentieth century that composers finally woke up to the real qualities of the bassoon as a solo instrument. More than anything, it is the range of characters and its astonishing versatility, so fancifully described by Sitwell, of which composers became fully aware and explored more than ever before. Voyage of a sea-god is an exploration over a period of exactly 100 years—a chronological musical journey through a century of astonishing changes politically, socially and artistically. The captain on this voyage, steering us through often very stormy waters, is this special musical voice: the sound of the bassoon.

1900

The turn of any century is inevitably a time for looking both forwards and backwards. In the year before Queen Victoria’s death, Britain was embroiled in the Second Boer War at the same time as investing in the future, the opening of the Central London Railway (now part of the London Underground’s Central line) being a significant example. The musical world mourned the death of Sir Arthur Sullivan, but also welcomed Alan Bush, Kurt Weill and Aaron Copland, all born in that year.

The English composer Richard Walthew, born in 1872, is a composer very much from the Victorian musical genre, and one who has suffered unjustifiable neglect since his death in 1951. A pupil of Parry, he became Professor of Music at Queen’s College, Oxford, and is best remembered for his fine output of chamber music—notably his Phantasy Quintet, published in 1912. He was also involved in the Conway Hall Ethical Society, and wrote programme notes for the South Place Sunday Concerts. His Introduction and Allegro for bassoon and piano was written in 1900 for the Sheffield-based bassoonist, instrument collector and concert promoter John Parr. The lyrical writing is voiced beautifully for the bassoon, set to an imaginative and skilfully written piano part that maintains a perfect balance between the two instruments.

1912

The major news stories of this year were the First Balkan War and the sinking of RMS Titanic. New musical horizons were being explored—Ravel’s ballet Daphnis et Chloé received its first performance in Paris, and a new figure from Russia was emerging in the form of composer Serge Prokofiev. During the time when he was composing his first piano concerto, Prokofiev was also working (intermittently, it seems) on a set of Ten Pieces for piano, Op 12. The ninth of these received a somewhat bizarre transformation in 1915 when the composer arranged it for a quartet of bassoons, under the title Scherzo humoristique. The humour is dark, with some agile fingerwork low in the bassoon’s register, contrasted by some glorious harmonies in a gentler middle section.

1921

With the world still reeling from the devastating effects of the Great War, it’s a sobering observation that the League of Nations was established in the same year Adolf Hitler became leader of the Nazi Party in Germany. The creative activities of that time underline the stark contrasts between looking back and forging ahead. The future was perceived to be with such groups as the Paris-based Surrealism movement and with the musical output of Les Six, much of which was despised by the composer once described by his colleague Charles Gounod as the ‘French Beethoven’.

The final works by Saint-Saëns—the Bassoon Sonata in G major, Op 168, and the Feuillet d’album for piano, Op 169—are stylistically firmly rooted in the nineteenth century. This is hardly surprising—he was born in 1835, quickly emerging as a musical prodigy, starting piano lessons aged two, and giving his first official public concert aged ten. It was eight decades later that he turned to the bassoon for some of his final musical inspirations. The sonata’s dedication was ‘à Monsieur Léon Letellier, Premier Basson de l’Opéra et de la Société des Concerts’. Given the musical and technical challenges of this sonata, Saint-Saëns really needed a player of the calibre of Letellier, who won the first prize for bassoon in the concours at the Paris Conservatoire in 1879. After a lyrical and highly expressive first movement, the bassoonist is plunged into a seriously challenging scherzo, where the superb Mozartian clarity of Saint-Saëns’s writing makes the music even more demanding—not least with a notorious low-dynamic ascent to the bassoon’s elusive top E at the end of the movement. The gentle mood of the third movement—slow, but with a brief, joyous concluding section—provides a welcome contrast. It features a beautifully crafted, often very sparse piano part which allows to the bassoon the fullest range of dynamics and colour.

1926

This year saw a major development in the musical world: the emergence of the first electrical sound recordings. Composer Hans Werner Henze, jazz musicians Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and actress Marilyn Monroe were all born in 1926. Despite the general strike in Britain, there was much creativity and enthusiasm for the arts, not least a production of Macbeth at the Princes Theatre (re-named the Shaftesbury Theatre in 1962) with Sybil Thorndike as Lady Macbeth. The music for this production was written by Granville Bantock, and is scored for the bizarre line-up of three bassoons, six trumpets, three trombones, three drummers and two pipers. Here we have premiere recordings of two of the bassoon-trio contributions. The first, a lament based on Act II Scene 2 (‘Methought I heard a voice cry, “Sleep no more! / Macbeth does murder sleep”’), is a beautifully simple, evocative piece written in Mixolydian mode. The second, drawing on the witches’ dance from Act IV Scene 1 (‘Come, sisters, cheer we up his sprites, / And show the best of our delights’), is a delightfully tongue-in-cheek composition based on the medieval Gregorian chant Dies irae which has been quoted by many composers, including Berlioz (Symphonie fantastique), Liszt (Totentanz) and in several works by Rachmaninov.

1936

Alongside the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and the Berlin Olympic Games (opened by Adolf Hitler), there was much activity in Britain in 1936, with the loss of two kings (one death and one abdication), and the gaining of the world’s first regular television service, from Alexandra Palace. On the night of the abdication of Edward VIII (11 December), a concert in London’s Aeolian Hall included the premiere performance of a new work by Arnold Bax: the Threnody and Scherzo for bassoon, harp and string sextet. This was a wonderful solo vehicle for the leading British bassoonist of that time, Archie Camden, who performed the work with the Griller Quartet and Frederick Riddle (viola), Eugene Cruft (double bass) and Maria Korchinska (harp). A review in The Times on 14 December makes reference to ‘the dark tones of the bassoon athwart the strings’—a fanciful wording that certainly describes the sombre mood of the ‘Threnody’. Bax’s addition of a second viola and a double bass to a string quartet creates an almost orchestral depth to the ensemble sound, beautifully complemented by the inclusion of the harp. The ‘Scherzo’ provides a welcome contrast, with an often muscular energy and some delicious harmonies. This work has rarely been performed since its premiere, partly because of its unusual (and in some ways impractical) line-up, but also because the score and parts for the work were all handwritten, with numerous errors and discrepancies as well as passages which are difficult to read. This recording was from a new Urtext performing edition which I prepared with the invaluable assistance of fellow bassoonist Miles Nipper.

1938

The general release of Walt Disney’s classic animated film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs must have been a rare and welcome moment of relief in the year that saw Hitler march into Austria and the notorious Kristallnacht. It was from this ghastly situation that composer Paul Hindemith (whose wife was partly of Jewish ancestry) had to flee, initially to Switzerland, and ultimately to the USA and a teaching post at Yale University in 1940. He had been denounced by Goebbels as an ‘atonal noisemaker’, and his music was banned by the Nazis who included it in the 1938 Entartete Musik (‘degenerate music’) exhibition in Düsseldorf. Little surprise, therefore, that one finds dark clouds in his sonata for bassoon and piano, composed in that year. Hindemith was never a heart-on-sleeve composer, but the juxtaposition of ethereal beauty and menacing harmonies must surely have emerged from deep-rooted anger and sadness at that time. Much of this is conveyed in his expressive piano-writing—the first section of the second movement is a good example. This leads abruptly into a march with some passages seeming to conjure up the horrific images of goose-stepping. There are of course lighter moments as well, and the angry energy of the march gradually subsides into a concluding pastorale, where the composer’s markings ‘Ruhig’ (‘calm’) and ‘Beschluß’ (‘decision’) are relevant in the same restrained way as the music itself with its mood of empty resignation, ending on a lonely minor chord.

1939

One hardly needs to be reminded of the war associations of this year, but creativity was also well to the fore with the release of the films Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz as well as the publication of John Steinbeck’s book The Grapes of Wrath. In the USA (which entered the war two years later, after the bombing of Pearl Harbor) a young composer was emerging, helped by the conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who in 1939 conducted William Schuman’s Symphony No 2. After the war, Schuman would become President of the Juilliard School (his activities including the formation of the Juilliard String Quartet), but in 1939 he was forging his career as a new composer on the horizon. Among his numerous compositions that year were the American Festival Overture, and a characterful Quartettino for four bassoons. Each of the four movements of the latter are short and contrasted, with some modal elements—an energetic ‘Ostinato’ where Schuman divides the ensemble into two halves, a plaintive ‘Nocturne’ exploring the wonderful blend of multiple bassoons, a certain dry humour in the ‘Valse’, and a celebration of the individual voices working together in the concluding ‘Fughetta’.

1942

Paris was not the place for Jews in 1942—the Germans forced the French police to round up more than 13,000 Jews who were then transported to the concentration camp at Auschwitz. To the east, the Battle of Stalingrad raged, as did Shostakovich in his seventh symphony, which received its premiere that year. Further west, the creativity was still flowing—the film of the year was Casablanca, and the musical contributions ranged from White Christmas (Bing Crosby) to A Ceremony of Carols by Benjamin Britten. Henri Dutilleux’s musical activities in Paris that year were as conductor of the choir of the Paris Opera, and as a fast-rising young composer. In later years he distanced himself from his earlier works, which were heavily influenced by the music of Debussy and Ravel, but his Sarabande et Cortège for bassoon and piano had already been published, and it has remained a firm favourite in the bassoon recital repertoire. Its technical demands are considerable, the requirements including the full three-and-a-half-octave range of the instrument. Understandably, given the events in Paris at that time, the mood is subdued—the ‘Sarabande’ conveys a somewhat empty lyricism with moments of anxiety, and the ‘Cortège’ could almost be a Hitchcock film soundtrack with its dark mood, paced progression and intermittent outbursts. It includes a hint of a fugue that goes nowhere, leading to a build-up, a cadenza ascending to a high F (top line of the treble clef), and a brief upbeat conclusion.

1945

The end of the war and the formation of the United Nations, 1945 was the beginning of a massive clean-up following major destruction—not least the bombing of Dresden, which destroyed much of the city, including the beautiful Semperoper (Saxon State Opera House). The music world mourned the death of Béla Bartók, but welcomed Benjamin Britten’s opera Peter Grimes at its premiere in London. Amidst all this, composer Herbert Howells celebrated the birthday of his bassoonist friend Hugh Crosthwaite, who invited Howells for a meal which included a rare wartime ingredient: a fresh egg. The composer’s response was a gift, in the form of this brief minuet with the title ‘Grace for a fresh egg’.

1952

A king dies—Britain says farewell to George VI and welcomes Queen Elizabeth II. The sense of a new post-war era was growing, with the arts very much to the fore. The seemingly never-ending play The Mousetrap began in London, British films included The Importance of Being Earnest with Michael Redgrave and music by Benjamin Frankel, and the first UK singles charts were published by New Musical Express. Yet, amid all this optimism, shadows remained—it was another two years before rationing ended, and the scars of blitzed cities were still very prominent. These contrasts are reflected in the first movement of the magnificent Concertino for bassoon and string orchestra by the Irish-English composer Elizabeth Maconchy. Tension created by the dissonances in the strings throughout this opening movement—not dissimilar to those in the sixth symphony by Maconchy’s teacher Vaughan Williams—is dissipated by a pacifying solo bassoon voice, sometimes lyrical, but also capricious. It is as if the bassoon were being the ‘oil poured on troubled waters’. This requires a wide range of expression from the soloist, and the dedicatee of the Concertino, Gwydion Brooke, was the perfect choice. As principal bassoonist to Sir Thomas Beecham in the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (and later principal bassoonist in the Philharmonia Orchestra), Brooke used his remarkable tone quality and musicianship to characterize and express through his playing in a way which was virtually unmatched at the time. Throughout the occasionally zen-like second movement the tension gradually eases, making way for an exceptionally agile finale—clearly a showpiece for the phenomenal technical abilities for which Brooke was famous. He made a BBC studio recording of the work in 1953 with the Goldsbrough Orchestra (which later became the English Chamber Orchestra) led by Emanuel Hurwitz and conducted by Edric Cundell. The premiere concert performance took place the following year at a Henry Wood Promenade Concert at the Royal Albert Hall, London, on 30 July 1954, when Brooke was joined by the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Malcolm Sargent. Bassoonist Stephen Reay made another BBC studio recording with the Northern Sinfonia in the 1970s, but—nearly seventy years after its composition—Maconchy’s Concertino is here receiving its first commercial recording.

1974

ABBA wins the Eurovision Song Contest with the song Waterloo, John le Carré blows open the world of espionage with his novel Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, and—sadly—many other things are blown apart by a series of IRA bombings, prompting a state of emergency in Northern Ireland. The musical world lost Duke Ellington, Darius Milhaud and David Oistrakh, but gained Annie’s song from John Denver. As an ambitious twenty-year-old student, I was attending a summer school in Canterbury in July that year, taking part in masterclasses at St Augustine’s College given by Stephen Maxym from the New York Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. Maxym was a legend among bassoonists—to this day he is regarded as one of the finest of all teachers on the instrument, and it was a real privilege to be able to perform in his masterclass. During the week, a local composer called in with the manuscript of a new work he had just written for solo bassoon. Unstoppable in my enthusiasm, I approached Alan Ridout and asked if I could play his new piece. Two days later, in an informal concert mainly for course players, I gave Caliban and Ariel its first-ever performance. Since then, I have played this more than any other solo piece, not only in concerts but also in a great many musical relaxation sessions for adult cancer patients. Ridout’s skill in his musical re-creations of the two Shakespearean characters in The Tempest is truly wonderful, revealing his detailed knowledge and understanding of the bassoon’s characteristics and using them to superb effect. The use of the lower-register articulation and angular intervals brings the character of Caliban to life—both the monster and, in Ridout’s gentler moments, Caliban’s human aspects. His use of the tenor register in ‘Ariel’, with evocative implied harmonies, paints a beautiful image of the airy spirit floating on clouds. Then, as Ariel takes off in flight, mercurial writing—mostly at a low dynamic—carries the listener on this effortless airborne journey over land and sea.

1985

Mobile phones were introduced, and Mikhail Gorbachev assumed power in the Soviet Union. The music world lost composers Roger Sessions and William Alwyn, as well as the pianist Emil Gilels, but gained An Orkney wedding, with sunrise from Peter Maxwell Davies, as well as Live Aid with Bob Geldof. In Eastern Europe, there were serious rumblings from the Polish Solidarnosc (‘Solidarity’) movement led by Lech Walesa, who had received the Nobel Peace Prize in October 1983. The Polish authorities were clearly unimpressed by this, and a year later—in October 1984—a popular pro-Solidarity priest, Jerzy Popieluszko, was tortured and murdered by three agents of the Sluzba Bezpieczenstwa (Security Service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs). At this time, composer Andrzej Panufnik was composing a concerto which had been commissioned by the American bassoonist Robert Thompson. In the composer’s own words: ‘I was deeply shaken and immediately decided to dedicate my concerto to the memory of this Polish martyr of faith and fatherland.’ Thompson gave the concerto’s premiere performance in Milwaukee in 1986, and recorded it the following year for the BBC with the composer conducting. Thompson also travelled to Poland in the same year, to give a performance at Jerzy Popieluszko’s church in Warsaw. The Polish authorities positioned an army tank by the main entrance of the church for the duration of the concert, but there was no incident, and the performance received an enthusiastic and emotional response.

The concerto is scored for a small orchestra of one flute, two clarinets and strings. Panufnik describes it as ‘an abstract work with no literary programme’, but he then goes on to describe the music: ‘Perhaps in Recitativo I (bassoon and three woodwind instruments) the listener might hear [the priest’s] humble prayer to the Virgin Mary. Possibly Recitativo II, where the bassoon is supported by the interjected chords of the string instruments, is related to the priest’s fatal encounter with the secret police—the very last interrogation before his tortured body was thrown into the Vistula river.’ The aria that follows is the longest movement in the concerto, and Panufnik describes it as ‘a kind of elegy, for which I composed a long melodic line in the spirit and character of Polish folk song, maybe invoking Father Popieluszko’s peasant origins’. The work is continuous. It is truly an astonishing addition to the solo repertoire for bassoon, a unique composition that places considerable demands on the soloist, and quite possibly the most powerful example in music of the bassoon’s incredible range and intensity of expression.

1991

This was a year dominated by major news events—the Gulf War, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the KGB in Russia. The arts lost many leading figures—Margot Fonteyn, Graham Greene, Peggy Ashcroft and film director Frank Capra—and specifically in music, the deaths of Andrzej Panufnik, pianist Claudio Arrau, jazz trumpeter Miles Davis, and the legendary Freddie Mercury, lead singer of the group Queen. Three prominent films that year were JFK, The Silence of the Lambs and Beauty and the Beast—and it was a composer closely associated with film music who was busy creating a remarkable new work for bassoon and piano. Richard Rodney Bennett had been for many years the President of Seaton Music Club in the southern English county of Devon. By the early 1990s he was well established in his adopted home of New York City, but he responded enthusiastically to a commission request from the music club for a new sonata, which was dedicated to me and my long-time recital partner Michael Hancock. In our preparations for the premiere performance, at Seaton, we had a session with the composer, who emphasized the importance of lyricism and flow in this music. The work is a fine example of what Tom Service was describing (in The Guardian, July 2012) when he wrote: ‘Bennett is living proof that … serialism and lyricism can not only co-exist but are dependent on each other.’ The influence of Bennett’s studies nearly four decades earlier with Pierre Boulez is ever present, and yet—although this music is in style nothing like any of Bennett’s film scores—the range of colours, textures and expressions makes this work every bit the equal of his finest oeuvres for the silver screen. The gentle flow of the first movement with moments of tension, the characteristic lilt of the ‘Forlana’ with its highly imaginative and animated piano part, and the drive and drama of the final movement that eventually dissipate into a reflective recognition—all these could be settings of scenes from a great film. This music has many fine qualities, but what I especially appreciate is the fact that it is a duo, not a solo with accompaniment. The bassoon and piano are very closely integrated throughout, and there are numerous passages where the bassoon takes an accompanying role with the piano very much in the lead. This sonata is a manifestation of a musical creativity that is rooted in and pays homage to the past, while taking those influences forward in new directions, creating new sound-worlds.

1999

At the end of an exceptionally eventful century, one glorious moment from its final year will forever stand out for those who experienced it. The solar eclipse on 11 August captured the imagination of many people, not least those who were present at Dartington College in Devon, England, where the International Summer School was in full swing. This was a location where the eclipse was total, and a large-scale musical project celebrating the event—Music of the Spheres—was being led by composer David Bedford in the Dartington College Tiltyard. David and I had worked together as summer-school tutors for several years, and his endless imagination, enthusiasm, originality and musical skills (partly fuelled by his work with John Peel and Mike Oldfield) were for me the source of great inspiration. During that week, David offered to write a solo piece for me; I was of course delighted, and requested an unaccompanied work. I mentioned that I was preparing a concert programme inspired by hills and mountains, to which his response (after a short pause) was: ‘I have an idea—I’ll work on it.’ A few weeks later, Dreams of Stac Pollaidh arrived in the post. I knew this would be special—he had an amazing gift for thinking outside the box, and Dreams of Stac Pollaidh (pronounced ‘stack polly’) is no exception. The inspiration for this piece is twofold—first, Stac Pollaidh the beautiful mountain in northwest Scotland with views of Assynt and the Summer Isles from its summit, and second, the Scottish pibroch, beloved of Highland bagpipers on special occasions. This latter link is a loose one—Bedford’s piece is a theme and variations, similar in some ways to a pibroch, but he takes the idea and develops it into a piece that can be seen as a miniature tone poem for solo bassoon. Beginning gently with a very simple melody (perhaps at the foot of the mountain), each variation thereafter becomes more elaborate and animated (the ascent) until we reach the peak, which is clearly a very breezy place! Then it all begins to calm down again (the descent), ending with a gently ornamented repeat of the original melody.

Coda

A solitary musical voice in the silence of a remote Scottish mountain, looking across towards the sea, admiring the complex coastline and magnificent landscape—could there be a better final destination for this remarkable voyage of a sea-god? As well as a celebration of the bassoon and all its incredible versatility and expressive qualities, this programme is also a celebration of great music—the thread that weaves together so many strands of our complex lives and experiences. The people, the creators, the places, the events—all are brought together on a musical journey led by the voice of the bassoon as it echoes its ancient ancestry, reflects on present times, and ventures forth into the future.

Laurence Perkins © 2021